Photo: Bonik Barta

Photo: Bonik Barta Neighboring

Myanmar has approximately 23 trillion cubic feet (Tcf) of gas reserves. At one

point, it was said that the country’s gas reserves would meet its domestic

demand for at least 150 years. For a long time, Myanmar exported surplus gas to

China and Thailand. However, the ongoing civil war has disrupted the country’s gas

extraction activities. Several Western companies have halted their operations

in Myanmar, leaving consumers to face a gas shortage despite the surplus.

Foreign

oil and gas companies once recognized Myanmar’s gas potential and invested

heavily in the sector. However, years of political instability and geopolitical

crises have jeopardized their operations in Myanmar. After the military junta’s

coup ousting the elected government in 2021, the country’s instability reached

its peak. Political disputes escalated into civil war, leading foreign

companies to withdraw their investments. The gas sector collapsed, and

electricity production also suffered.

Bangladesh

was also once considered a gas surplus nation. The country has a proven gas

reserve of about 30 trillion cubic feet (Tcf), though over 21 Tcf has already

been extracted. Various foreign surveys have suggested that Bangladesh may have

even larger reserves. Colorado-based consultancy firm Gustavson Associates

presented a report in 2011 estimating the country’s potential gas reserves at

38 Tcf, with a 50 percent probability of reserves exceeding 63 Tcf. Despite

this report, the government dismissed Gustavson’s findings. No steps were taken

to explore these potential reserves. Instead of pursuing exploration, the

government increased dependency on imports, exacerbating the gas sector’s

crisis.

Energy

experts believe that both Bangladesh and Myanmar have always had significant

potential in the gas sector. Once seen as surplus nations, Myanmar now

struggles to extract enough gas due to its civil war, while Bangladesh has followed

a policy of LNG import dependency instead of investing in gas exploration and

extraction. Both nations are now facing severe crises in their gas sectors,

with energy security risks becoming more prominent in their economies.

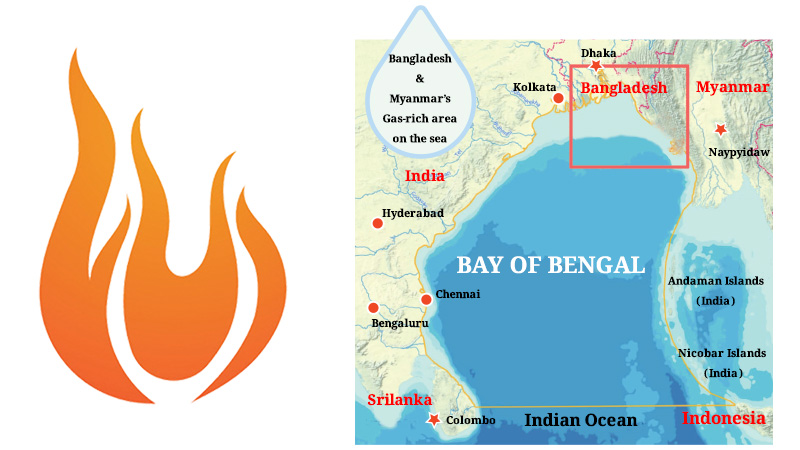

The

Myanmar government has recently taken the initiative to invite international

tenders for oil and gas exploration in the Bay of Bengal. Additionally, it has

restructured its energy plans to rely on domestically extracted gas. Similarly,

Bangladesh issued an international tender for oil and gas exploration in the

Bay of Bengal this March, with several multinational companies expressing

interest. However, there are concerns that the Rohingya crisis could hamper

exploration activities in the Bay of Bengal for both Bangladesh and Myanmar.

Geopolitical analysts believe that unless the Rohingya crisis is resolved

peacefully, the resource extraction process in the Bay of Bengal is likely to

face significant disruption.

In

Bangladesh, Chevron’s Bibiyana gas field remains the largest supplier to the

national grid. Chevron also operated in Myanmar but decided to withdraw its

investment as the country’s political instability following the military coup

began to shift towards civil war. Most recently, in April of this year,

Thailand’s state-owned fossil fuel extraction company PTT Exploration and

Production Company (PTTEP) announced that Chevron’s subsidiary Unocal Myanmar

Offshore Company (UMOC) had withdrawn its investment from Myanmar’s largest gas

project, Yadana. PTTEP and local partner firms have since taken over UMOC’s

share in the project. According to media reports, gas reserves in Yadana are

nearing depletion, and the civil war has made it impossible to ramp up

extraction and exploration activities in other fields in Myanmar.

Bangladesh

has a long history of gas exploration. The first tender under the PSC framework

was issued in 1974 after independence. However, international oil and gas

companies became more active in the 1990s. Two international tenders were

issued during this time under the PSC framework, resulting in the discovery of

five gas fields. In 1993, Petrobangla signed agreements with multinational

companies to explore eight gas blocks. Under the PSC framework, the US company

Occidental was awarded exploration rights for blocks 12, 13, and 14, while

Dutch-based Cairn Energy signed agreements for blocks 15 and 16. Additionally,

Rexwood Auckland was awarded blocks 17 and 18, and United Meridian was awarded

block 12.

In

1997, Petrobangla issued another international tender for larger-scale gas

exploration on land under the PSC framework, covering four blocks. Shell and

Cairn Energy jointly explored block 5; Unocal Corporation explored block 7;

Tullow and Chevron-Texaco explored block 9; and Shell and Cairn Energy jointly

explored block 10. The exploration in block 9 led to the discovery of the

Bangura gas field, where Tullow found 1,100 billion cubic feet (Bcf) of gas.

From

2008 to 2012, under the jurisdiction of the PSC (Production Sharing Contract),

several offshore blocks were opened for tender in Bangladesh. In 2008, joint

ventures between ConocoPhillips and BAPEX aimed at exploring gas in DS-8 and

DS-10 blocks. However, these explorations did not yield any significant

discoveries. Subsequently, until 2012, tenders were invited for three more

blocks. In blocks SS-4 and SS-9, BAPEX collaborated with the Indian company

ONGC Videsh, while in block SS-11, joint exploration was conducted between

BAPEX and Santos-KrisEnergy. These endeavors also failed to uncover any new gas

fields.

In

2016, under the Quick Enhancement of Electricity and Energy Supply (Special

Provisions) Act 2010, the government leased blocks DS-10, DS-11, DS-12, and

SS-10 to South Korea’s POSCO Daewoo Corporation. However, apart from ONGC

Videsh, most other companies eventually abandoned these blocks.

According

to energy expert and geologist Professor Badrul Imam, the lack of substantial

gas exploration in Bangladesh primarily stems from a lack of interest. He

highlighted to Bonik Barta, “The focus was more on imports than on discovering

reserves. As a result, while gas was consumed, no significant initiatives were

taken to secure reserves. Various internal and geopolitical factors also played

a role over the years. Following the resolution of the maritime boundary

dispute with Myanmar, Bangladesh had a significant opportunity for large-scale

gas exploration in the sea, but this opportunity was not utilized. Conversely,

after resolving their maritime boundary, Myanmar brought in foreign oil and gas

companies and found gas reserves. For more than two decades, internal and

geopolitical challenges hindered Bangladesh’s exploration efforts. Despite

strong prospects of finding gas, many areas remained unexplored. If these areas

had been investigated, Bangladesh could have confirmed whether gas existed or

not. After settling the maritime boundary with Myanmar and India, both

countries found gas reserves through exploration, but Bangladesh, for reasons

unknown, failed to conduct similar explorations.” Professor Imam blamed this

inaction on a lack of interest and a focus on import-dependent policies.

The

maritime boundary dispute with India was resolved in 2014. Although 10 years

have passed since then, Bangladesh has not shown any significant activity in

deep-sea exploration. Meanwhile, India has made considerable progress, with

state-run Oil and Natural Gas Corporation Limited (ONGC) discovering large

deposits of oil and gas earlier this year in the deep sea, just 35 kilometers

off the coast of Andhra Pradesh.

On

the other hand, it has been 14 years since Bangladesh settled its maritime

boundary with Myanmar and 10 years with India. During this period, Bangladesh

has seen no success in oil and gas extraction in the deep sea. Experts accuse

the country of delaying exploration and focusing too heavily on

import-dependent energy policies. While Myanmar and India have ramped up

efforts and secured foreign investments, Bangladesh has remained stagnant,

resulting in its vast maritime energy resources staying untapped.

Former

BUET professor and energy expert Ijaz Hossain told Bonik Barta, “Myanmar had

made some progress in gas exploration, but internal issues like military rule

have hindered their progress. On the other hand, Bangladesh has largely failed

in its gas exploration efforts. The country has always been skeptical about the

existence of gas reserves, leading to decisions influenced by politics and

geopolitics. However, there were opportunities to bring in large foreign

companies for exploration. Bangladesh

missed out on significant potential.”

For

over two decades, the gas sector has seen minimal investment, leading to an

increase in import dependence. Exploration in the country has mostly been

conducted by the state-owned company BAPEX. Since the company’s inception, there

has been investment of a total of BDT 40 to 50 billion in exploration and

surveys.

From

2009 to 2024, the Energy Division claims to have discovered six new gas fields.

In this period, 21 exploration wells, 50 development wells, and 56 workover

wells have been drilled. Additionally, six-thousand kilometers of 3D seismic

surveys have been conducted, along with the construction of 1,355 kilometers of

gas transmission pipelines and facilities for oil storage and supply pipelines.

Currently,

Petrobangla is drilling 50 wells as part of the ongoing gas exploration efforts

in the country. By mid-2025 to 2028, it plans to drill at least 100 more wells,

with an estimated cost of around BDT 200 billion.